3D Printing and Intellectual Property: Are the Laws Fit for Purpose?

3D printing, like any other industry, is fraught with intellectual property law considerations at all levels. These range from 3D printing hobbyists who must respect copyright when uploading and sharing file designs, to multinational companies who guard their scientific discoveries with patents and marketing designs with trademarks. Parties are not affected equally by these laws: those with a higher stake (monetary or otherwise) in intellectual property face larger repercussions if they do not respect the regulations. Many individuals and organizations consider the laws to sometimes overly favor large companies to the detriment of smaller ones and individuals, and seek reform to make the industry more just. Here, we will look at the different perspectives of this concern, and the people and institutions involved on all sides of debate.

In order to study intellectual property and its relation to 3D printing, we must first define the terms. The World Trade Organisation defines intellectual property as ‘the rights given to persons over the creations of their minds’. Within this falls two categories: copyright, which offers ownership rights to original creations (by people or companies, where the person created it as part of their job) and industrial intellectual property, which includes trademarks, patents, and trade secrets. Let’s take a closer look at each one to understand what it means.

Photo credit: Getty

An Overview Of the Key Terms

What is Copyright?

We can trace copyright law all the way back to 16th century Britain. Attempts at standardization came with the Berne Convention, ratified in 1887, which saw 10 signatory states agree to the automatic protection of created works for 50 years after the author’s death. More recently, EU copyright law offers protection for 70 years after the author’s death, granting economic rights (control over the work and remuneration) and moral rights (right to attribution and right to integrity). In the US, the situation is similar; works created after 1978 with a known author are protected under copyright for 70 years from the author’s death, commonly known as life + 70. These copyright laws do of course apply to 3D printed designs: they can protect the relevant file from which prints are made. It should be said that copyright protection applies to aesthetic or design aspects of a part; useful objects or the useful components of objects are not protected under copyright but can be protected with patents and trade secrets.

Industrial Production: Patents

The other aspects of intellectual property law relate to industrial production. A patent is a form of works protection which is granted for, among others, machines and processes which are novel, nonobvious, adequately described and clearly claimed by the author. The first recorded modern patent was granted in Florence in 1421, and today they exist in abundance in the manufacturing industries, including 3D printing. Once the application for a patent is approved by the overseeing organization, for 20 years from filing others must apply for a license to make, use, or sell the invention. This protection comes in exchange for its public disclosure.

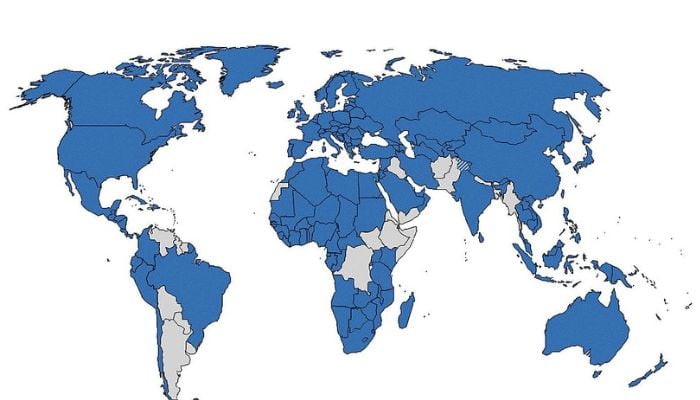

Patents are mutually beneficial to both parties: the creator has a monetary incentive to innovate, and external researchers can focus on new creations using the knowledge gained from the patent’s obligatory publication: as the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) puts it, there is no need to reinvent the wheel, so to speak. Patents are not universal, but parties wishing to seek international patent protection can make a single application under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), administered by WIPO. This single patent application applies to the over 150 countries part of the treaty – known as Contracting States – which include the US, Canada, much of Africa and almost all of Europe, and also China, a major player in the 3D printing market.

WIPO and its European counterpart EPO (European Patent Office) were formed in the 1980s to simplify the patent process. Many 3D printing firms today benefit from the PCT to protect patents in multiple countries, from solution manufacturers like Stratasys and General Electric, to companies which use these solutions like Boeing and Airbus.

WIPO Patent Cooperation Treaty member states as of 2021. (Photo credit: WIPO)

Trade Secrets

For firms which wish to protect their innovations, but these innovations are either not patentable or are best kept undisclosed, they can make them trade secrets. These can be protected with legally enforceable contracts such as Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs), and are advantageous over patents as they are cost-free as no registration is required, and can last indefinitely. One of the best known examples outside of 3D printing is the Coca-Cola recipe, a secret since 1891; within 3D printing, NDAs are used (among others) by service bureaus, which will be covered later in this article.

Trademarks

A further aspect of IP law are trademarks. A trademark is a sign which distinguishes the goods of one company from those of another, and is normally owned by the company who uses the mark. One well known example in the field is FDM/FFF printing; while the technology is informally known as FDM, in fact this term was registered as a Stratasys trademark in 1991 after its development by co-founder Scott Crump. When trademark infringement occurs, the other party (the plaintiff) can file a lawsuit for monetary damages. In theory, firms today must still avoid using the term ‘FDM’ in favor of ‘FFF’ or ‘extrusion’, as the trademark is still active, while the patent expired in 2009.

Copyright Law and 3D Printing

Copyright law often relates to individual makers in the 3D printing world, including creator-made design files on host sites such as Thingiverse, Cults, MyMiniFactory, and Printables. These sites have seen a spurt in popularity in recent years, with Thingiverse growing from 2.3 million to 6.2 million users between 2018 and 2022.

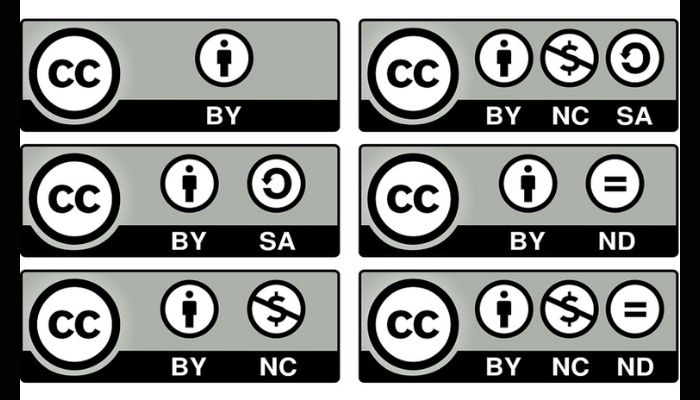

Files on these sites are offered under a number of licenses, including Creative Commons. These are public copyright licenses overseen by the eponymous non-profit organization, which are recognized worldwide. These six licenses offer a way for creators to explicitly claim legal rights over their work while allowing others to benefit from the creations. For the purposes of 3D printing websites, this means mesh files from which prints can be made.

Users can choose whether to allow commercial use and adaptations (‘derivatives’) of their work according to how they want the file to be used. Indeed, CC Australia offers copyright holders an interactive flow chart to help them choose the most appropriate license according to their wishes.

Creative Commons licenses. (Photo credit: Systeme D/Creative Commons)

It is important to not lose sight of the bigger picture: millions of individuals use these 3D printing file websites and in most situations copyright laws pass without event. We spoke to Andrew Stockton of 3D modeling site Titancraft, one of the top creators on Thingiverse in terms of downloaded files. Firstly, he explained that his choice of Creative Commons license depends on the reason he made the file. “If I made the object for fun, I use CC0 or Attribution license. If I’m not planning on making money from it, I figure let people do what they want with them. If it’s related to my business (gaming miniatures) I use the No Commercial license.”

As shown, intellectual property laws affect people in 3D printing differently according to their business niche. As Mr Stockton’s 3D printing models are valuable for customization rather than the file themselves, he is less affected by people choosing to use them without attribution, but for someone whose business involves the files themselves, infringement of copyright laws is a far more significant problem. It is important to remember that one’s stake differs depending on their circumstances.

In turn, the other user may be a great deal more concerned depending on the entity whose files they are using. They would likely act far more attentively if they were using licensed material from a large organization than from an individual (which is common: in 2017 Disney sparked debate after requesting the removal of Star Wars files from Thingiverse, and in 2022 Honda requested the same of 3D Printer manufacturer Prusa for all files bearing the former’s name). Nevertheless, a quick glance at Thingiverse today shows many files bearing trademarked logos, suggesting indeed that the law is not applied the same to all users.

When Copyright Infringement Allegations Led to Legal Action

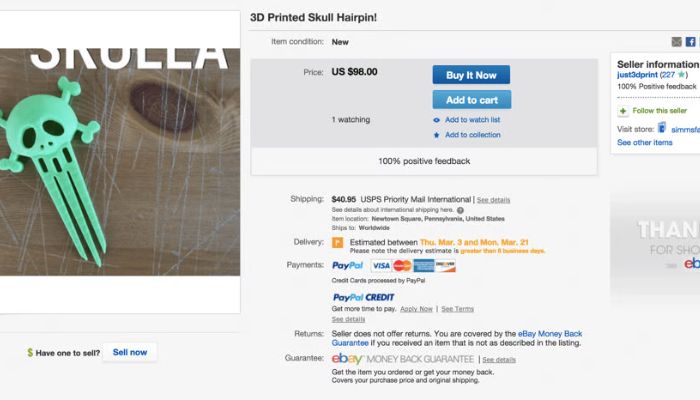

With the growth of the sites, the intellectual property concerns have grown correspondingly. While most everyday usage of the files passes without incident, there have been high-profile situations of complex legal battles in the 3D printing world involving copyright law. In 2017, a scandal broke when Just 3D Print took multiple STL files from Thingiverse and uploaded them as Ebay listings. When the uploader of the files asked Just 3D Print to remove them, Just 3D Print responded that they were now in the public domain.

The situation continued with lawsuits from Just 3D Print against various outlets: Stratasys, 3DR Holdings, and TechCrunch. This was for the ‘defamatory’ nature of their coverage of the situation. These outlets had claimed that the actions taken by Just 3D Print constituted a violation of copyright; the articles in particular by TechCrunch and Stratasys were alleged by Just 3D Print to have cost them the loss of a product line which would have made them $2,000,000 per month. In the end, these lawsuits ended up being found against Just 3D Print, save for the case against Stratasys.

One of Just 3D Print’s ebay listings

According to Michael Weinberg, a former Shapeways lawyer who was also Vice President of PK Thinks from the Public Knowledge foundation, these cases were not related directly to the question of whether or not Just 3D Print had infringed on copyright. In the case of Techcrunch, the defense was that of them being opinions, not qualifying as defamation (as well as statute of limitations). For 3DR Holdings, the court found that there was no defamation and even if so, their actions were ‘unrelated’ to any harm experienced by Just 3D Print. This case shows that intellectual property law notwithstanding, firms can be liable for legal action based on statements of opinion and demonstrates how quickly a situation can spiral from coverage of possible copyright infringement to allegations of defamation.

The State of Patent Law in the 3D Printing Industry

As mentioned above, patent law is an important part of innovation in industrial 3D printing. The first patent in the field was granted in 1984 to Chuck Hull of 3D Systems Corporation for his Stereolithography Apparatus (SLA) technique. Since then, the number of patents has increased rapidly as companies are determined to protect their innovations and emerging technologies.

Between the years 2015 to 2018, AM patent applications grew at an average annual rate of 36%, which is more than ten times faster than the average yearly growth of patent applications at the EPO (European Patent Office) in the same period (3.5%), and in 2020, 800 were filed. Between 2010 and 2018, patent applications were most common in the field of health (with 907 in 2018), followed by energy, then transportation (with 436 and 278 applications respectively in the same year).

The numbers are made up of a number of firms, with the top 3 being General Electrics, United Technologies, and Siemens. As for the USA, in 2020 the businesses with the most patent applications were as follows: Hewlett Packard Development (HP) – 470, General Electric (GE) – 331, and Kinpo Electronics – 273.

Chuck Hull, the inventor of the first 3D printer. (Photo Credit: National Innovators Hall of Fame/3D Systems)

How Does Patent Law Affect Businesses?

With the continuous rise of 3D printer manufacturers and startups developing new technologies, patent law continues to have an impact on the industry, but its effect on businesses is often not discussed enough. Firstly, unlike rights automatically conferred like copyright, patents must be applied for – and they come at a price. Legal resource BitLaw puts the cost of a US patent between $15,000 and $20,000. Certain fees within the process are almost essential, such as the fee incurred for the search of patent databases to make sure that the new idea is truly original (indication to the contrary is known as ‘prior art’). Furthermore, administrative fees are an obvious part of making it onto the official patent lists. These sometimes prohibitive costs mean that (in theory) only inventions which are truly worthwhile will become patents, but also mean that smaller firms can struggle to protect their inventions using intellectual property laws.

One extremely well known case of patent infringement allegations was 3D Systems vs Formlabs in 2012, in which the former accused the latter of infringement of several patents, including a stereolithography patent granted to 3D Systems in 1997. This ended with an agreement in which 3D Systems granted Formlabs a license to make and sell Formlabs products under the 3D Systems patents in question. In exchange, Formlabs agreed to pay a royalty of 8.0% of net sales of Formlabs products throughout the period that the license is in use.

What Steps Do Firms Take To Protect Their Inventions?

According to US-based 3D printer manufacturer Desktop Metal, the risk of asserting your patent rights as a company is third party lawsuits which, in the case of decisions being made against the firm, could result in huge cost and the other party using your technology against you. Therefore, some firms turn to alternatives to patents, including changing production locations in order to protect classified information. Desktop Metal’s annual report for the fiscal year 2020 said ‘Key consumables used in various print processes, such as proprietary resins and binders, are developed and produced either in-house or with core partners to ensure protection of intellectual property and production that meets our formula and specifications’.

Firms are protective of their trade secrets when entrusting them to service providers. We spoke to Christina Perla, co-founder of service bureau MakeLab, a firm which offers 3D printing services in New York. She told us that although being a service provider does not cause complications in the sense of copyright – the creators of the file own the rights to it, even if MakeLab is making the file a reality – many of the files which MakeLab is entrusted with are considered trade secrets. Therefore, the company takes sensible measures to avoid file defrauding, including NDAs where necessary. These files are also shared only with the relevant employees. The lengths which these 3D printing firms go to to protect their intellectual property shows the importance of secrecy in the industry, and the value placed on trade secrets as a way of unofficially protecting ideas.

Christina Perla is head of Makelab in New York (photo credit: Downtown Brooklyn)

Firms can face legal consequences not only from their contemporaries, but also from the government. Various US government departments recently fined the service bureau 3D Systems up to $27 million for sharing design documents, blueprints and technical specifications with its then-subsidiary in China to facilitate 3D printing; this constituted nineteen violations of the Export Administration Regulations (EAR) .“Today’s enforcement action highlights a troubling trend of U.S. companies offshoring 3D printing operations and ignoring the export controls on the technical data sent overseas to facilitate the 3D printing,” said OEE Director John Sonderman.

Improvement and Reform: Organizations and Individuals

There are many key organizations which fight for change to the intellectual property laws as they stand – not just in a 3D printing context. The aforementioned Creative Commons is in favor of a reform of copyright laws. It wants the public to have easier access to culture and knowledge in order to facilitate their vision of ‘‘universal access to research and education and full participation in culture’, and wants to help overcome ‘legal obstacles’. To this end, its licenses are deliberately free, simple, and standardized. Another group with a similar aim is Public Knowledge, a US-based non-profit which promotes freedom of expression and an open internet through supporting consumer rights and promoting creativity through balanced copyright.

Unlocking 3D Printers

Creative Commons is not the only example of an entity which wishes for reform. The aforementioned Michael Weinberg has a profile relating to many 3D printing legal concerns, among them the movement to ‘unlock 3D printers’. This would mean that the machines are no longer programmed to only work with certain materials, but are restricted only by practicality rather than the company’s preset regulations.

Every three years the US Copyright Office considers petitions for exemptions to the regulations of Digital Rights Management (DRM), outlined in this case in Section 1201 of the 1998 Digital Millennium Copyright Act. This is to allow groups with good reason to break these digital locks to do so. In 2017, Michael Weinberg filed a petition to lift the restrictions to the rule to allow 3D printer users to unlock their printers in order to use their own choice of material. He frames it as a desire ‘to eliminate copyright law from any discussion about third party materials in 3D printers because copyright law does not belong there’.

In 2018, he reported an opposition by Stratasys; the latter claimed, among other things, that closed systems are necessary to ‘mitigate risks involved in the use of a specific material, such as fire hazards or hazardous fumes’. The ruling in favor of Mr Weinberg’s petition to remove the limitations preventing users from ‘unlocking’ their 3D printers was extended in 2020. Note that this means that in the USA, users cannot be sued for using their own materials on their 3D printers, with the caveat of the exception being available ‘solely for the purpose of using alternative material, not for the purpose of accessing design software, design files, or proprietary data.’

The RepRap Movement Offers Democratized 3D Printing

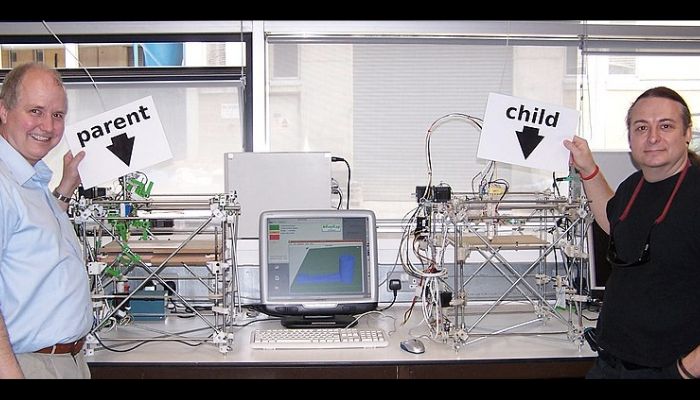

If copyright law is criticized by organizations like Creative Commons, other movements also take issue with lack of democratization. Take for example the Maker Movement, a social trend towards the development and sharing of creations and design files. Projects such as RepRap, founded at the University of Bath by Adrian Bowyer in 2005, offer freely available self-replicating machines, licensed under the GNU General Public License (GPL). The technology has been the cornerstone of companies such as Prusa Research.

Mr. Bowyer’s motivation, aside from pure curiosity, was to invest power in individuals by allowing them the opportunity to build for themselves. He also mentioned the choice of GPL as it ‘employs copyright to facilitate opening the sources of a project in a way that obliges subsequent developers also to open them similarly’. The RepRap project did not face patent controversy, despite using FDM/FFF technology. This is because, under European patent law, research into patented technology can be considered fair use.

Interestingly, according to Mr. Bowyer it was he who invented the term FFF after a request from Stratasys to not use the trademarked FDM. The popularity of the RepRap movement shows the appeal of a democratized 3D printing world among consumers – if not companies – and also shows that this can be achieved with relative ease, given the existing exceptions and suitable licenses available. A further non-profit example is the Projet FabricAr3v from a multidisciplinary consortium funded by the EU. This project is based on a Metal Injection Molding-like technology and using granules as a material. This project aims to provide lower-cost machines for organizations like SMEs or Fablabs and universities.

Adrian Bowyer (left) and Vik Olliver(right) with a parent RepRap machine, made on a conventional rapid prototyper, and the first complete working child RepRap machine, made by the RepRap on the left. (Photo credit: RepRap)

Copyright law aside, patent law and 3D printing also has its detractors. There are also concerns among legal professionals that the standard for patents is too low. According to Dr. Lukaszewicz, in her PhD law thesis titled ‘The Maker movement meets patent law’, almost half of patents are actually non-valid – that is, they do not meet the required standards to be registered patents. In this thesis Dr Lukaszewicz outlined her aim to work on patent reform in her scope as a legal expert. Some consider patents to detract from innovation and to suffocate smaller companies out of the market, as they cannot develop their own processes based on a patented technology.

Findings: Is It Time for Reform?

Intellectual property law is an unavoidable part of 3D printing for hobbyists, small businesses, and major industry alike. In theory, the law is designed to protect innovation and encourage creative pursuit. In fact, there are often complex legal situations in which anyone from small-scale mesh file designers to massive multinational conglomerates can find themselves at risk of legal action. Furthermore, the law often rules in favor of these larger companies and rulings can sometimes be considered to be overly hostile to open creativity (as stated by the Creative Commons organization).

Other individuals and organizations such as Public Knowledge lead long-term battles for open access to creative works, and hope for the modification of copyright laws for the sake of public use. In terms of the 3D printing industry, there is also the protection of intellectual property and a strong focus on its importance for innovation and commercial success, which can lead to controversial and nuanced cases and rulings. Overall, the application of intellectual property laws in the world of 3D printing is a complex and nuanced issue which is likely to grow in importance as the field expands.

What do you think of the current intellectual property laws in 3D printing? Let us know in a comment below or on our LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter pages! Don’t forget to sign up for our free weekly Newsletter here, the latest 3D printing news straight to your inbox! You can also find all our videos on our YouTube channel.

So eye-opening, I had not considered all the complexities of copyright in 3D printing! It seems a very delicate topic as it’s important to share knowledge, particularly in fields such as medical applications of 3D printing, whilst also protecting small businesses and individual creators from having their ideas profited from to their detriment

Nice article. This is especially important for us as a 3D modeling and 3D scanning company. When we are designing prototypes, we signs NDAs which protect our clients from the 3D modeling process all the way to manufacturing.

Good article ) on the other hand, contrary to a widely spread idea, it is not Chuk Hull who filed the first patent on 3D printing but three French researchers (Alain le Méhauté, Olivier de Witte and Jean Claude André, three weeks earlier.