How Can 3D Technologies Help Solve Crimes?

It’s a common motif on both movie screens and TVs: a murder is committed and the police investigate to find the culprit. The most modern techniques are used and the culprit is usually quickly arrested. And of course, this has roots in reality. Every year, almost half a million people worldwide lose their lives as a result of deliberate homicide. In 2023, the homicide clearance rate in the United States was around 50%, but these rates vary from country to country. Additionally, 3D technologies are playing an increasingly important role in investigative work and forensic science, generally contributing to its success. Today, very few homicides are not investigated using 3D reconstructions or 3D scanning techniques.

3D forensics is an essential component of modern forensic science. It involves the reconstruction, analysis and processing of criminal acts using 3D tools and human decisions.This autonomous field is increasingly used in criminal law and to solve crimes.To better understand the role of 3D technology in investigative work and the analysis of forensic evidence, we spoke to a number of experts.

3D technologies are increasingly used directly at crime scenes (photo credits: APA/Georg Hochmuth).

The Use of 3D Technologies in Forensic Science

3D technology makes it possible to collect and analyze not only digital media, but also physical evidence, such as printed objects. This can be done via 3D scanning and additive manufacturing.

The Role of 3D Scanners

Photogrammetric measuring systems have been used in investigations since the 1930s and, since the late 1990s, short-range photogrammetric systems have been widely used in forensic science. They open up new possibilities, particularly for measuring crime scenes, but also for determining the size of criminals. Today, laser 3D scanning is used in almost all countries. The Hamburg State Police confirms: “3D scanners are regularly used in police work to assess or compare event locations and/or physical objects, including in digital form.”

Various scanners are used in crime scene documentation, including stand-mounted and mobile scanners.Here, an Artec portable scanner is in use(photo credits: Artec 3D)

3D forensic analyst Eugene Liscio, who has already solved cases in Canada, the USA and Europe and teaches at the University of Toronto, adds: “The four main scanning technologies are photogrammetry, laser scanning, structured light scanners and application-based scanning.”

Photogrammetry creates photorealistic texture networks and, combined with surface images, CT scans and MRIs, provides a detailed 3D view of the body. Wounds can thus be enlarged, analyzed and compared with crime scene instruments or shooting directions.

3D scans are divided into volumetric and surface scans. Volumetric scanning enables high-resolution images to be taken, and requires special software and specialist knowledge to create 3D models from the data. Surface scanning is more user-friendly, as only surface details are captured and integrated software is used. It is reliable for post-mortem injury analysis and for the Landmarking Method.

The Landmarking Method uses marker points in images or data to create precise reference systems, enabling accurate measurements and comparisons. In addition, photogrammetric data is collected using drones or DSLR cameras to create a 3D model of the crime scene. The entire reconstruction can be visualized using virtual reality via VR goggles or a virtual reality space.

3D reconstruction of a crime scene.The blood spatters depicted make it possible to calculate the location of the attack (photo credits: Sophia Lavcanski)

Area 54.2 of the Landeskriminalamt Nordrhein-Westfalen (LKA NRW), which is responsible for measuring, reconstructing and visualizing crime scenes, explains: “The use of 3D laser scanners enables three-dimensional digital preservation of crime scenes, as well as retrospective analysis and reconstruction of the course of events, e.g. calculation of volumes, determination of the field of view and direction of fire, and determination of the size of criminals”.

How 3D Digitizing Is Used to Conduct a Survey

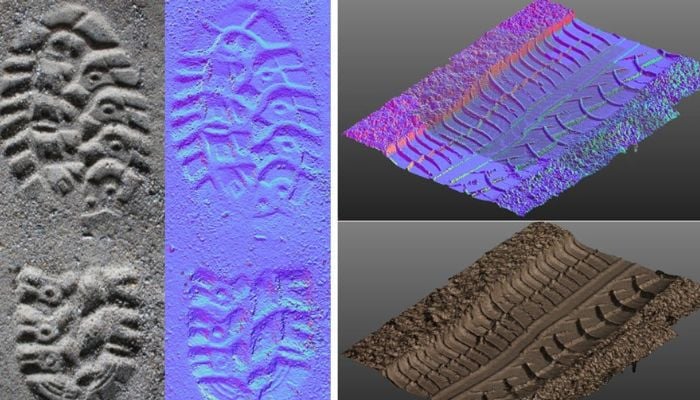

Investigators use 3D scanners by placing them over the footprints or tire tracks and starting the recording. At the same time, a camera attached to the scanner takes a picture. A few seconds later, the user can see a preview on the built-in screen to check whether the image is in focus. Detailed analysis then takes place in the laboratory, where trassologists examine the length or depth of the profile and compare the tracks with other crime scenes.

The 3D scan of the forensic evidence using the portable 3DF scanner (photo credits: Fraunhofer IOF)

The Role of 3D Printing

3D printing has been used in the forensic field since the early 2010s to reconstruct evidence, with the choice of printing technology depending on the intended use. Resin printers are ideal for detailed models, while powder bed fusion can be used for robust parts. However, it is FDM 3D printing that is most often used, as it is inexpensive and versatile.

North Rhine-Westphalia’s LKA comments: “3D printing technology is used exclusively as a technical tool for creating so-called trackable targets, which are used for digitizing the movements of people or objects.” Hamburg’s LKA, which does not yet have a 3D printer, also explains that 3D printing can be used for the physical examination of digital objects.

3D replica of a spine from a murder case in which a woman was killed. The bone would have been difficult to produce using traditional manufacturing methods. The print was made on the Creality CR10-V3 3D printer (photo: Eugene Liscio).

The Potential of 3D Technologies

3D technology offers forensic science and investigative work better analysis possibilities, and therefore the chance to find and arrest the right culprit. North Rhine-Westphalia’s LKA confirms that 3D scanning technology has had a lasting impact on investigative work, particularly homicide commissions, throughout the country.

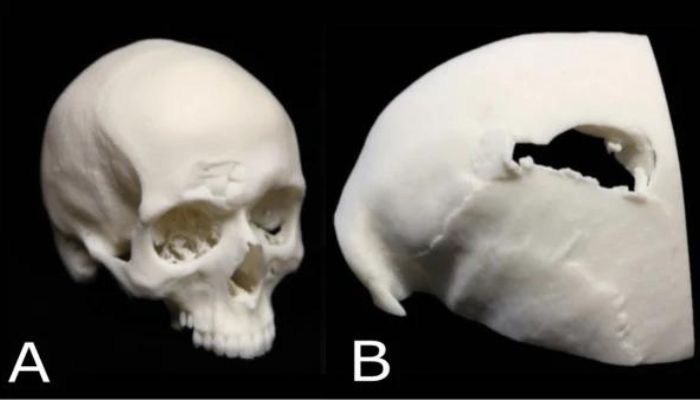

Joe Mullins, renowned forensic artist at the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, also points out, “With today’s methods, we can process a skull scan with the authority retaining the remains and print the skull on site. Recently, I had a skull scanned from Barbados, which was then 3D printed in Virginia and had a facial adjustment made in New York. This would not have been possible 20 years ago.”

The making of a skull (photo credits: Joe Mullins)

Thanks to the development of technical and digital possibilities, up to and including a visualization technique using VR glasses or a VR cellar, investigators can take a three-dimensional tour of a reconstructed crime scene. Views from different perspectives are accessible here, stresses LKA NRW.

They explain: “The observer is thus no longer in the role of the outside observer, but is instead able to virtually enter the crime scene and immerse themselves in the digital representation and reconstruction of the course of the crime. The integration of the most diverse 3D data enables interactive visualization of case files, and the knowledge thus acquired can have a decisive influence on the evaluation of traces, testimony and links between facts, which would be impossible without adopting this angle of view.”

Laser 3D scanners enable investigators to visualize the crime scene on computer, even after leaving it, and to confer. The Office of the Criminal Police confirms: “This opens up the possibility of apprehending the crime scene realistically, getting to and moving around the crime scene without first having been to the actual scene of the event.”

This enables investigators and those involved, such as the court, to simultaneously visualize the virtual crime scene and discuss it together. The technology makes it possible to keep an overview of the event and identify bullet impact angles, even in the case of gun crimes or chaotic car accidents.

3D reconstructions of the crime scene make it possible to visit it even after leaving it (photo credits: Jeremiah Crowell).

What’s more, the technology prevents damage to the evidence when it has to be transported. The technology is useful for facial reconstructions, as the traditional method involves superimposing clay and plaster on the skull in order to reconstitute it. This process is repeated several times, damaging the skull. 3D technology eliminates the need to touch the skull and creates a computer model in which, using software programs, the clay reconstruction is imitated, a virtual reconstruction is made and 3D printed replicas can then be produced.

Even in the field of forensics, where shoe or tire impressions are usually cast in plaster, a time-consuming procedure that destroys the trace, the use of 3D scanning can help overcome these challenges and preserve the traces.

For Mullins, the biggest advantage is that the originals are preserved: “Whether it’s a skull or an important piece of evidence, we can avoid problems. In the field of forensic art, it has already happened that a skull has been lost. Setting up a procedure in which all skulls are scanned, printed and photographed serves as a safeguard in case something happens to the original.”

Results of a 3D scan using the 3DF scanner (photo credits: Fraunhofer IOF)

Current Use of 3D Technologies in Survey Work

3D technology has many applications in investigative work. Liscio explains that forensic work comprises three main components: documentation, analysis and visualization. In this context, 3D printing serves as a documentation product and visual aid.

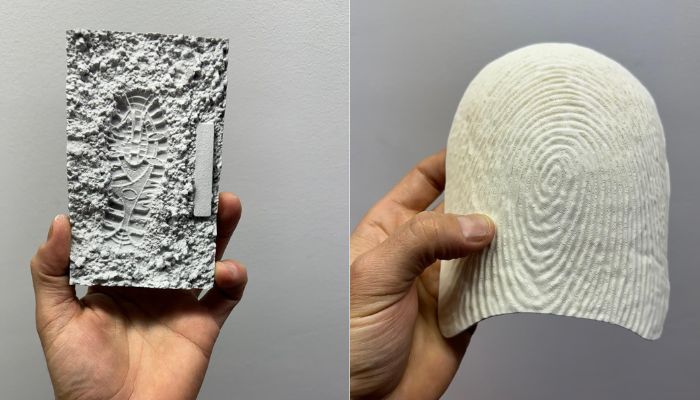

3D printing is mainly used to reproduce evidence, thus preserving real evidence. For example, a victim’s finger can be reconstructed in 3D to unlock technical devices. In court, 3D-printed reproductions, such as skulls or weapons, are useful for clearly illustrating injuries and the course of events.

Liscio points out, “Normally, we don’t bring bones to trial, but we could bring a replica. For example, a weapon can be printed to explain to judges, jurors and other investigators that this is the weapon used. Currently, 3D technology is being used to demonstrate the crime and help people understand it. Everyone learns in different ways. Seeing an image on a photograph is fine, but having something in your hands and being able to look at it helps. 3D printing is also used as an educational tool in the field of forensic medicine, to provide anatomical representations to medical staff.”

3D-printed replicas of a shoe print and an enlarged fingerprint (photo credits: Eugene Liscio)

3D scanning technologies also make it possible to reconstruct entire crime scenes, to understand their position and the objects in them, and to illustrate them visually. As LKW NRW explains: “In the context of crime scene documentation, the recording of crime scenes using 3D laser scanners is a complementary and sometimes firmly integrated means of police work at crime scenes.”

The Department of Criminal Science and Technology at Hamburg’s LKA also uses measurements taken with 3D scanners to digitally represent and reconstruct a wide variety of crime scenes.

Gradually, 3D technology is also being used in the field of forensic archaeology. It offers great potential in this field, as it enables us to represent what objects might have looked like before. Research is underway, for example, to reconstruct burnt bones using 3D printing.

The use of 3D technology in investigations has led to significant progress in several cases around the world. A remarkable example occurred in Ohio, USA, where the face of a recovered skull was reconstructed using the Clay Tools program and then 3D printed. This enabled investigators to verify identities and move the case forward. A

nother event was the infamous suitcase murder in 2015, for which a combination of scanning and 3D printing was used for the first time. West Midlands Police worked closely with the University of Warwick’s Manufacturing Group to use 3D technology to analyze charred bone fragments and determine that they belonged to the suitcase being examined. This plays a crucial role in victim identification.

Examples of 3D-printed skull parts in fatal head injuries (photo credits: Errickson, D., Carew, RM, Collings, AJ et al.)

The Legal Position: 3D Replicas in Court

A study conducted by the Cranfield Forensic Institute has revealed that the rate of understanding of the technical language used in the courtroom when presenting 3D printed models has improved to 94%, compared with 79% for photographic images. However, the use of 3D technology to document crime scenes is not yet regulated by law.

Lawyer Jens Ferner, who as an IT lawyer deals with 3D copyright and developments around 3D technology, confirms: “There are no clear legal guidelines for public or private investigators, in the sense that the way in which documentation must be carried out is regulated. On a procedural level, this issue is addressed at the level of the exploitation and evaluation of evidence: poor documentation can lead to it being denied probative value, or even prohibited from being exploited. In this context, certain documentation standards have developed among government investigators, but they are not prescribed by law.”

Main Challenges for 3D Technologies in Forensic Science

One of the biggest challenges for 3D technology in survey work is the time and cost factor. Liscio explains: “You have to choose the right tool for the job. Sometimes this means investing in different tools or renting scanners because you don’t have the right tools. It’s not easy to go from scanning to 3D printing. There’s a lot of work in between, and it’s often a challenge, because we’re dealing with very complicated and delicate parts that require a lot of assistance.” This means that an investigator has to become an expert in this field, learning new working procedures and how to use the tools.

3D scan of a shoe print (photo credits: Artec)

The LKA NRW confirms the same: “Documenting a crime scene using a 3D laser scanner is a time-consuming process, requiring close coordination with those working on the scene at the same time. What’s more, the use of this technology generates large quantities of data that can only be processed and visualized by high-performance computers and software.”

They also point out that the time required to process data for evaluations, crime scene reconstructions and visualizations is justified by the benefits the technology brings to investigative work. The specialist department at Hamburg’s LKA sees the lack of uniformity in data and printer formats available on the market, as well as the need for large storage capacity, as a challenge.

Future Developments

As 3D technology develops and becomes more accurate, it is expected to be used more and more in investigations. Liscio points out that 3D printing is known in the forensic field, but is not yet widespread, which could change as accuracy requirements increase.

Mullins is also convinced that 3D printing will be used more frequently in the future: “The technology is advancing so rapidly that 3D printing will become the norm to support investigations. It will continue to help solve cases, but at a faster pace.”

3D scanning with the Artec Eva (photo credits: Artec 3D)

Despite the possibilities and advances, there is still a long way to go before 3D technology can support survey work to its full potential. An important step here would be the training of investigators through training programs. In addition, ongoing research is needed to adapt the technology to the requirements of investigative work, and to facilitate collaboration between technicians, lawyers and investigators.

In the long term, 3D technologies have the potential to facilitate investigative work, put criminals behind bars and solve crimes more accurately. But to achieve this, we need to continue laying the foundations through training and research.

What do you think of the role of 3D technologies in forensics? Are they a new tool for our experts? Let us know in a comment below or on our LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter pages! Don’t forget to sign up for our free weekly newsletter here for the latest 3D printing news straight to your inbox! You can also find all our videos on our YouTube channel.

*Cover Photo Credits: APA/Georg Hochmuth