3D Technology in the Restoration of History

There are numerous initiatives today showing how 3D printing helps art and history. This can be through creating complex shapes and new works, educating a wider audience, or preserving artefacts. By recreating a ruined monument for example, we preserve its heritage and there is a concrete interaction with the past that would not have been previously possible.

This is further expanded upon by several professors and doctors at the Harvard Semitic Musuem. They state that “modern digital 3D visualisation makes possible the full-scale virtual reconstruction of ancient architectural remains which survive today only as damaged or partially preserved ruins. Using digital animation, adding color and lighting effects, it is possible to show how these sites and monuments changed through time, from their original construction and ancient use to their eventual abandonment and destruction.”

A trend supported by a report published in 2014 by a team of Austrian researchers entitled “3D Printing for Cultural Heritage” shows how 3D technologies are key to integrating a new sensory dimension into museums.

Reproducing History

When preserving artifacts, care is key. But, even with care, the process is still difficult. With 3D technology, we can do this sometimes without even disturbing the object. Furthermore, we can replicate pieces that are no more.

Reconstructed Palmyra Arch in Trafalgar Square

A recent example comes from Syria, when the ancient city of Palmyra was under siege by ISIS. Many of their cultural artefacts had either been destroyed or greatly damaged. Through 3D printing, we are bringing these collections back, producing 3D replicas to retain Palmyra’s culture. An example of this is shown with the 3D printed arch of Palmyra, which was erected in London’s Trafalgar Square in 2016 as an act of defiance against ISIS’ terrorism. The 6 metre tall reconstruction weighed 11 tonnes, and was recreated from 2D pictures of the original arch. Italian company Tor Art rebuilt the arch with 2 robots developed by RobotMill. These robots built the different blocks, which were then assembled in London’s Trafalgar Square, as well as in New York and in Dubai.

The Lady of Cao

3D printing people is another area helping reproduce history – by bringing back our ancestors. An example of this can be seen in Peru, where a team was able to bring back the mummified remains of “The Lady of Cao”, the first known female ruler of the Moche civilization. Scientists found some of the remains of the Lady of Cao in 2006. Using Faro Technologies’ 3D virtual reality scanner, they were able to scan her body and recreate a 3D image that was then used to 3D print her. This took 10 months with an iPro 8000 SLA 3D printer from 3D Systems.

3D scanning the Lady of Cao

Milagros Arquiñigo from the Fundación Wise commented that they assembled “an international team of experts made up of archaeologists, anthropologists, forensic scientists, dentists and 3D technology engineers, to build a 3D digital model of the mummy, print a 3D replica and, using specialized software and anthropology techniques forensic, perform the facial reconstruction that would reveal to the world, for the first time, the face of The Lady of Cao.”

Restoration for Future Generations

Following the French revolution many items in Versailles were stolen or destroyed, including pieces belonging to the last reigning monarchs of France. Through a project conducted by the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, historians were able to recreate a chair owned by Marie Antoinette using molds, 3D scanning and 3D printing. By scanning the missing parts, they were then able to reverse 3D print them. Using moldings taken from the 3D printed pieces, they were then able to recast it in a non-chemical material. This was then toned and gilded so that it would match the original pieces.

The 3D model made to fit the chair

The model was copied from the intact side of the chair

Replication for Education

The British Museum 3D prints a large amount of artifacts each year. The museum has given the world access to more than 4,700 artifacts online since 2014; allowing people to 3D print them straight from home. The British Museum worked with Sketchfab to upload 3D models using a method called photogrammetry. This is when multiple photos are taken in a strategic pattern around the object. These models can then be used for 3D printing or VR. The museum then worked with English 3D printing company ThinkSee3D to sell models in the museum shop. Replicas like the Statue of Roy and the Statue of Antinous now sell for £200 and £250 respectively.

3D technologies involved in creating these reproductions

Although the British Museum has been one of the pioneers, there are other projects with the same aim. These include ‘Scan The World’, a project created by MyMiniFactory in 2014 with the aim of bringing art to the masses. The collection now includes 3D models for sculptures available in the Getty Center, The Louvre, Vatican, and has accumulated over 21,000 printing hours worth of famous sculptures. This marks a huge contribution in accessibility in a range of areas such as education and preservation.

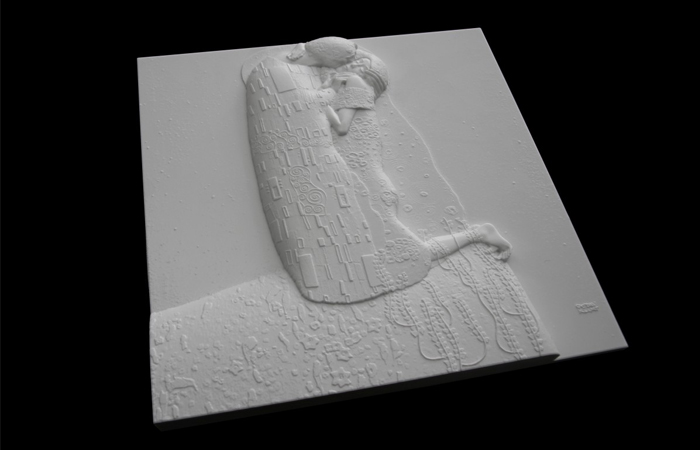

‘The Kiss’

The second main trend is opening the world of museums to touch. For centuries, museums have been a place to look and learn, but not to hold or feel the items. This trend is now being reversed due to 3D printing, providing new opportunities to museum patrons. An example of this can be seen at the Belvedere Museum in Vienna, where they have 3D printed ‘The Kiss’. This is a famous painting by Gustav Klimt. The project came about through the EU’s Access to Museums for Blind and Visually Impaired People (AMBAVis). By turning the painting into an ‘interactive tactile relief’, visitors can truly interact with it.

3D version of ‘The Kiss’

The 42cm x 42cm painting includes unique finger tracking technology, so that when certain parts of the painting are touched, audio information will play. Through the use of sensors that are incorporated into the piece, visitors are given a multisensory experience as the art literally talks to them and explains the different aspects of the painting to them. Through the use of both touch and sound, the museum enables blind visitors to partake in the museum experience. This is huge as it is bringing history alive, regardless of if people can see the art or not. 3D printing is therefore enabling a closer relationship between visitors and exhibits.

Conclusion

These examples depict how 3D technologies are helping reproduce, restore, and educate the masses on history. 3D modeling, digitization and printing are changing how we access the past. Whether you have limited access to museums because of distance, lack of resources, time, or more severely because of a disability, the new digital tools available to museums ensure you can still access history. This is an example of physical and digital words overlapping, tearing down barriers worldwide. 3D printing and scanning is opening up the world, one museum at a time.

Have an opinion? Let us know in a comment below or on our Facebook and Twitter pages! Sign up for our free weekly Newsletter here, the latest 3D printing news straight to your inbox!