3D-Printed Ceramic Monoliths Can Purify Water By Removing ‘Forever Chemicals’

Worldwide, 2.2 billion people do not have access to a safe drinking water supply and a further 3.5 billion people do not have adequate sanitation facilities. This data, published in the latest United Nations World Water Development Report, confirms the need for concrete action to ensure healthy living conditions and access to water. And one of the biggest challenges in the water crisis is the problem of pollution. Litter, plastic in the oceans, run-off of chemicals and industrial waste into groundwater and many other human activities are affecting the quality of our water supply. Numerous companies are now specializing in proposing solutions using innovative technologies. One of the latest examples uses 3D-printed ceramic monoliths to purify water from so-called forever chemicals.

Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are one of the most commonly used families of chemicals in industry today. PFAS are also known as forever chemicals because they take up to 1000 years to decompose. These substances are used in various consumer products because they are resistant to water, grease and fire. Examples of products containing these substances are Teflon pans, cleaning agents, grease-resistant paper, textiles and others. Despite their usefulness, PFAS are harmful to health. Studies have shown that PFAS cause thyroid disorders, hormonal changes, developmental and cardiovascular problems and increase the risk of cancer and diabetes.

Photo Credits: Chemical Engineering Journal

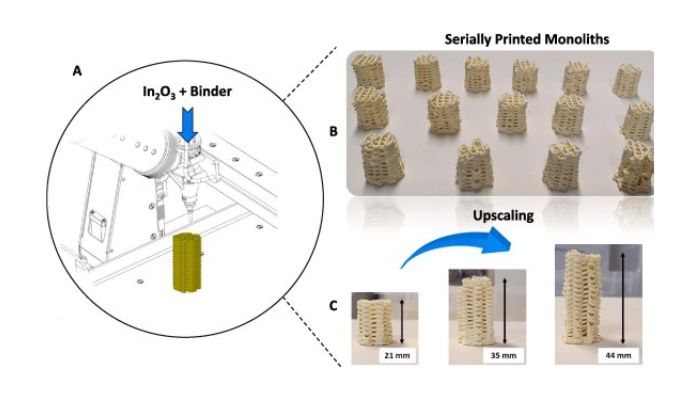

But this may no longer be an issue. A team from the University of Bath in England has found a solution that removes at least 75% of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), one of these PFAS, from water. They invented tendril-shaped monoliths that are 3D printed with ceramic. The results of this study are promising and the developers see their product as an effective and scalable new tool for removing chemicals from water.

Removing PFAS With 3D Printed Ceramic Monoliths

But how does this work? Well, the ceramic monoliths are about 4 cm long and are in the shape of a grid. To make them, the ink used in the 3D printing is impregnated with ceramic indium oxide. This material, when placed in PFAS-containing water, immediately adheres to the monoliths. Thus allowing the chemicals to be removed in under three minutes.

Dr. Liana Zoumpouli, Research Associate in the Department of Chemical Engineering at the University of Bath, further explains: “Using 3D printing to create the monoliths is relatively simple, and it also means the process should be scalable. 3D printing allows us to create objects with a high surface area, which is key to the process. Once the monoliths are ready you simply drop them into the water and let them do their work. It’s very exciting and something we are keen to develop further and see in use.”

The process used to produce these ceramic monoliths was material extrusion. The printer used was the Lutum®5 ceramic 3D printer from VormVrij. The latter is a Dutch-based manufacturer of ceramic 3D printing solutions. As mentioned, the monoliths have a lattice design and the study showed that they can be reused after an initial cleaning of PFAS. To reuse them, they simply need to undergo a high-temperature “regeneration” heat treatment after each use.

Extruder of the Lutum®5 (photo credits: VormVrij)

Tests in this first phase have shown that the printed monoliths can remove 75% of PFOA from water and that their manufacture and use is compatible with existing water treatment plants in the UK and elsewhere. In the future, the researchers will continue to refine the monoliths and hope to use them on a large scale. This study was published in the Chemical Engineering Journal, you can read the full paper HERE.

What do you think of using these 3D-printed ceramic monoliths for water purification? Do you think they could be the solution to these so-called ‘forever chemicals’? Let us know in a comment below or on our LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter pages! Don’t forget to sign up for our free weekly newsletter here for the latest 3D printing news straight to your inbox! You can also find all our videos on our YouTube channel.

*Cover Photo Credits: University of Bath